AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION TO SECOND EDITION

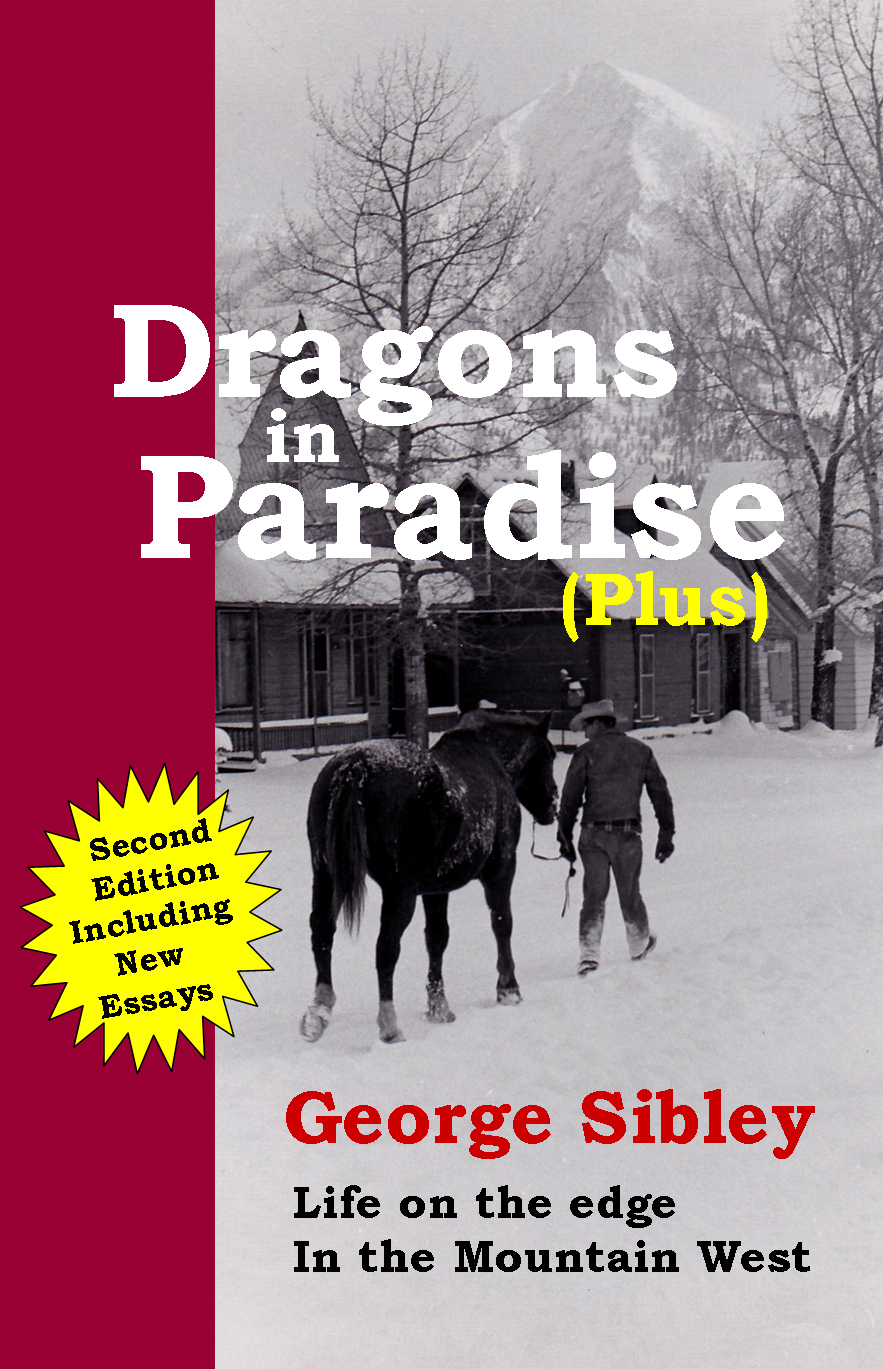

This is the second edition of a collection of essays, stories and poems first published ten years ago, and reprinted twice. The decade since 2004 has seen some cultural changes – among them, the coming-of-age of on-demand printing, which makes it pretty affordable to consider another printing without finding a publisher to commit to another thousand books or so. I’m grateful to Raspberry Creek Press and Larry Meredith for wanting to keep Dragons in Paradise available.

But since the book needed to be reformatted anyway for a print-on-demand process, it seemed like a good time to clean up and prune some of the shaggy writing, and also to add a few new pieces that seem to fit with what’s already in the book. The new essays herein include one on climate change, which is emerging as the challenge of the century; a collection of essays about modern life that doesn’t include some meditation on the cultural meaning of that challenge seems to me to be lacking something essential. There is also some musing on mortality (fitting enough for someone now in his seventies), a Dionysian look at bars, something about sleeping with a forest fire, and a couple reflections on friendship.

Not a new book then, but an old book with a new look and some new content. I can excuse this by noting that Walt Whitman spent most of his writing life reissuing Leaves of Grass with new content. Not that I’m trying to put myself in that league.

There’s another change over the past decade that I want to note here, in introducing or justifying or apologizing for a new edition, and that is a loss: the “demise” of the original publisher of Dragons in Paradise, Mountain Gazette Publishing, not coincidentally also publisher of the Mountain Gazette magazine in which most of these essays first appeared. I put “demise” in quotes, because there are entities that from time to time disappear, but never really die – King Arthur comes to mind, or Count Dracula. Mountain Gazette has been that kind of a phenomenon. I want to spend a minute on Gazette history, in hopes that someone might pick up this book and get inspired to repeat what Fayhee characterized as his “lunacy,” for a new generation of mountain writers.

The Gazette first emerged in 1972, as the expansion or maybe the transformation of a ‘60s publication called Skiers Gazette – to the “ski industry” what gadfly “indie” papers like the Village Voice were to the mainstream media. The genius behind first the Skiers Gazette, then the Mountain Gazette, was Mike Moore, a Denverite who seldom skied or hiked, never climbed, and hardly did anything outdoors in the mountains except play golf. What he did do was read a lot in an omnivorous way, and he found what he saw as an ornery freshness in the writing of often desperate people who were hanging out in the mountain towns, or out beyond in the mountains themselves. People like myself. That is roughly why he turned his job as editor of the Skiers Gazette turned into a vision of a magazine “generally about the mountains.” “Why not?” he asked rhetorically in the first issue in 1972.

One reason “why not” turned out to be finding advertisers who wanted to push their wares in a magazine whose content, as often as not, was written by dreadlocked dirtbags who lived out of army surplus gear and made fun of the expensive stuff in the ads. For most of the 1970s, George Stranahan of Woody Creek near Aspen, was the Gazette’s “angel,” but Moore left the magazine in 1978, and at the end of 1979 Stranahan pulled the plug on the Gazette, concluding that it would never achieve economic independence, let alone profitability.

The Gazette had, however, gained a somewhat devoted following among people who hung out in mountain places – including a college student in New Mexico’s mountains, M. John Fayhee, who became a writer, reader and by extension editor himself after college. Fayhee tells his own story about his relationship with the Gazette in his “Foreword” here. But I did not realize how much I’d missed the Gazette myself, reading it and writing for it, until Fayhee revived it late in 1999 – again with George Stranahan’s initial help – getting the first issue out on the cusp of the new century: Same black-and-white format on newsprint; the original Gazette had ended with issue number 78; the first issue of the revival was Mountain Gazette 79.

It was not, however, just a nostalgic oddity; the “new” Gazette just picked up where the original had left off, with many of the same writers (myself among them) glad for the chance to again “write with the leash off.” Fayhee kept the publication going for almost 14 years, under a series of new owners, all imagining that they could solve the old problem of advertising for an unconventional publication. Finally in the spring of 2013, the last owner folded the print version. The Mountain Gazette still exists in an online version, but Fayhee has left it to pursue his own writing projects.

I loved the Gazette because the Gazette editors, Moore and Fayhee, loved the kinds of things I write and like to read, and indulged me by publishing just about everything I sent them. “Indulgence” is no exaggeration; neither editor ever complained about length, even though my essays occasionally went to five or six thousand words. Once Moore gave me 20 magazine pages for an essay. He joked about my occasional eructation of guilt at writing so long, and my occasional promise to cut something down; “Sibley,” he told other writers, “can always cut a 2,000-word story down to 2,500.”

Nor did they expect or even want standard “journalism” – that business of doing “objective” interviews with other people to get other people to say what the journalist wants to get said. Their standard was basically “tell your own story,” and take the time and space to tell it right without any B.S. (or at least not too much). Their idea of “editing,” beyond ex post facto correcting of spelling and grammar, was to throw out an idea, either to a specific writer or to the whole stable – setting everyone off on a “bar issue” or a set of essays around “What is a mountain person?” It may have been more “The New Yorker” of the mountain culture than the “Village Voice.” Any editor can cut and paste; not all of them can inspire.

What they were doing was giving writers the opportunity to “essay.” Yes – the verb form of the word.

We tend to use “essay” as a noun, describing a discrete piece of writing – according to my dictionary, “a literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.” But a second meaning is “an effort to perform or accomplish something, an attempt.” And that leads to a transitive verb, “to essay,” “to try, attempt; to put to the test, make trial of.”

So the Gazette was a publication not so much for “essayists” as for “essayers.” Essayers are those for whom E.M. Forster’s observation on writing is more of a charge: “I don’t know what I think until I read what I’ve said.” Yes, exactly. Essayers essay forth into the unknown, the underbrush by the path, the road less traveled, the ignored past, the rejected future, and if you start out knowing where you’re going to finish, you’re not really essaying.

Myself, I was not in the mountains out of any huge enthusiasm for hiking, biking, boating, floating, skiing, fishing, climbing, camping, or any of the ways of testing oneself against nature, although I engaged in all of that to some degree because, as Hillary (Sir Edmund, not Madame) said, it was there, and it’s what others who were there were doing too. Why was I there? I was there in retreat, a gradual withdrawal to the edge-zones of a civilization I had grown up enfolded and nurtured by (Wonder Bread built strong bodies eight ways), but had ceased to really understand.

What I didn’t know when I retreated to the upper Upper Gunnison Valley in 1966, is that I was an early participant in a demographic phenomenon: the “nonmetropolitan population turnaround.” For the first time since – well, probably the 1830s, more people were moving out of the metropolitan areas surrounding America’s great cities than were moving into them. This phenomenon has ebbed and flowed from the late 1960s to the present – fluctuating with a lot of economic variables.

The most consistent recipients of these “post-urbanites” have been places that have significant recreational components in the local economy. Places like the Upper Gunnison Valley where I landed nearly 50 years ago, and have not since been able to successfully leave for long. I have done many things here and in adjacent places over those decades – ski patrolman, newspaper editor, forest-fire fighter, bartender, sawmill operator, academic oddjobber at a small college – but mostly what I’ve done is essay around a nexus of questions that all seem to be variations on “what are we doing here?” Not just “here in the Upper Gunnison,” but here on earth, all of us? What is the human project? Is there a human project? And if there isn’t, why were we made to be conscious of, and able to alter so fumblingly, this incredible mix of beauty, madness, meanness, glory, love and hate, fear and foolishness that is our planet?

Somedays, I get up in the morning and go to work at some bit of business or another. But other days, I get up – or just stop in the middle of some bit of business – and get back to essaying. This book is the tracks of some of that essaying. It’s my hope that you will find it interesting and maybe challenging – I like it best when I so irritate or confuse a reader that they look me up for a beer, which I will always buy (hoping of course that they actually bought the book).

While I have your attention, I need to thank a few people: Mike Moore and John Fayhee first and most for all their indulgence in the Gazette and giving me permission to go ahead and just write; Ed and Martha Quillen and now Mike Rossi for another often indulgent publication, Colorado Central magazine; Sandy Fails of Crested Butte magazine who has given me a lot longer leash than that kind of magazine usually does; and Art Norris and Don Bachman who pushed me from “wanting to be a writer” to “write or else” with the Crested Butte Chronicle. (I was a lousy newspaper publisher, a terrible ad salesman, and too undisciplined to be a good reporter, but that experience – four or eight empty pages a week – sure taught me how to be a writer.)

Then there are all the people who have put up with me and my often erratic ways – my partner Maryo Gard with whom the first beer of the evening is the best part of the day; my first wife Barbara and our two offspring Sam and Sarah who may change the world as much as they’ve changed me; and all the day trippers and campfire sitters and 12 to 2 riders of the night who keep sharpening me up for the work that we’re still trying to figure out, the work that’s actually worthy of us and this planet we’re trying not to destroy before we can find out – well, what William Stafford said: “Your job is to find out what the world is trying to be.”

***