Dispatches from the Map

Sherri Anderson

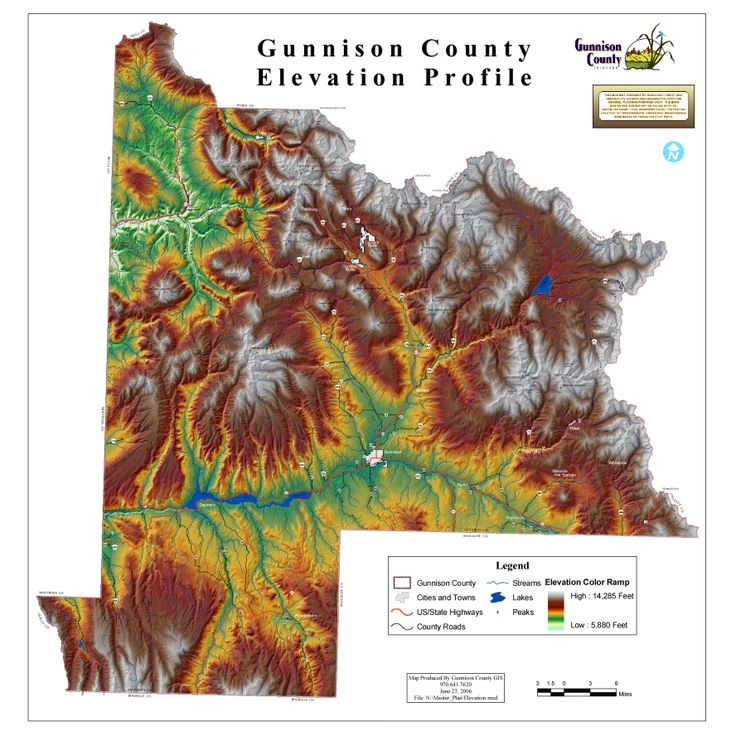

The goal is simple. Every red road and labeled single track under my own power. No motors. No cheating. Cover every Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management road, every numbered dirt bike and hiking trail represented on an old tourist map that I bought on my first day in Gunnison twenty years ago. Whether I run them, bike them, ski them, hike or snowshoe them, so long as my legs are the means of propulsion, it counts.

I began this quest sitting atop a sage hill in Long’s Gulch. Looking out at the undulating, quilted landscape, I wondered where the hell I was. I had set out for a run, connecting the braided roads of intersecting drainages and gullies willy nilly. A left here, an ascent of a dusty two track there, I meandered along the contours of the landscape, occasionally checking my surroundings, the little yellow flowers punctuating the shrubby, brambly scene. Taking a break, absentmindedly chewing a sticky granola bar, I unfolded the waxy map that I had recently re-discovered on a shelf in the hall closet. The bark of a sage bush poked the back of my thigh, the blue Colorado sky infinite.

Transposing the topographical lines onto reality, I oriented myself, retracing my circuitous route with my finger. Rotating both myself and the map several times, I realized I could simply head a little further to the west, cut down one of the many numbered roads and save myself nearly four miles. Happy and self-satisfied with my powers of deduction, I considered the network of jeep trails linked like capillaries, miles and miles of interconnected routes marked simply by brown, wordless metal signs, buoys in an ocean of sage.

Wiping the August grime off my forehead with the back of my hand, I hypothesized. Given enough time,.could I manage to propel myself, motorless, along every one of these roads? Could I accomplish such a huge goal and not be crushed under the weight of mom guilt? Travel every trail east of Dillon Pinnacles and west of Monarch Pass? If methodical and persistent, could an employed person tick off every unpaved path from Schofield to Saguache?

Would anyone in my house think to replace the toilet paper?

Even if it turned out to be impossible, it seemed worth trying. At the very least, I’d see some very pretty places and I certainly couldn’t be any worse off for the effort. And with that, I began a pursuit that would confound my friends and add a lot of miles to the family car.

I became obsessed with the south basins of Gunnison County first. The massively intricate web of lines on my map presented initially as a perplexing and seemingly nonsensical entanglement of roads both rough and smooth. As I pedaled and pounded along them, I slowly began to make sense of their patterns, the numbering schema, their loose logic.

I would come home, highlight the day’s accomplishment with a Sharpie and stare at the map, strategizing. My deepening understanding lifted a three dimensional world off of wavy lines and circles. That summer I went further and further, day after day, marking off spurs and linking giant loops; leaning heavily on my thighs as I ascended stupidly steep roads that marched straight up the face of a hillside with no regard for reason whatsoever; driving forty five minutes to walk thirty minutes along a dead end track, the ruts evaporating into thin grasses. I spent a lot of time with cows and my own thoughts.

Gradually, my circle of interest widened. Parlin Flats, Woods Gulch, Saguache County, East Elk Creek. Entire swathes of the county that I had spent years flying past at seventy miles an hour began to reveal their secrets to me. Lush cottonwood oasis tucked deep in the folds of an exposed and dusty gulch, the sea foam green of a sage forest in bloom, antelope that peer from above like gnomes, hidden accesses that may see ten people all year.

Once, while pedaling along the top of a ridge just east of Doyleville, a bobcat ran directly in front of my mountain bike, disappearing off the steep drop into the brush below. I stood astride my bike, my mouth hanging open as the sky blushed a deep pink.

I have spent the last four years marking my map. After work, on the weekends- three, five, ten, and, when I’m lucky, twenty miles at a time. Week after week, I slowly chip away at a goal that I greatly underestimated. While it can at times seem downright quixotic, my pursuit has come to define my recreation and imagination. Our county is so large and encompasses so much public land, truly I’m not sure if I will ever finish it all. If I do, I have no real sense of how long it will take me. I completed the most immediately accessible areas in those first few summers, and as the years and Sharpie marks go by, the distance to the unmarked gets further. There is just no good way to get to Mount Tilton under your own power in the winter.

But I am determined and the pursuit has become far greater than the sum of its parts. In four years, your children enter and graduate from high school, scores of feelings get hurt and heal, opportunities are taken and left to pass by. The mundanities and the triumphs of one person’s life tracked along ridgelines and seasonal creeks. I have seen supermoons rise behind rock walls, phantom mountain lion tracks in the spring mud, wildflowers exploding like confetti in wet alpine meadows, mushrooms the size of my head. Some of these miles have been explored with dear friends; the vast majority have been logged alone.

This endless exploration has taught me how the features of this incredible valley are intimately and inexorably connected. I’ve learned to decipher the numeric code of the Bureau of Land Management, obsessing over GPS coordinates like a pirate with a sextant. At times, when taking shelter in a bush from a spring hail storm on the side of an impossibly steep hill on the way to an abandoned mining claim with only the goal of turning around and going back the way I came, I wonder if I really am a crazy person. But even if it is a lunatic’s dream, it is mine. I like to cynically joke that my map may be the most interesting thing about me.

My map is heavily weathered, tearing and sections are held together with tape. The folds are deep and fading. I am aware that I could do the same thing on Strava, creating my own little reality show for others to follow and compete with. But that is not what I set out to do on that hillside.

I never lie to myself. I cross reference Garmin readings and compass bearings and walk all the way to the end of every spur. If I get back to my kitchen counter and realize I came up just short, it only gets marked to the point that my ruler and string can confirm. There are hills I have climbed seven times just to get to the bottom of a mysterious and sometimes decommissioned intersection. I am acutely aware that no one but me knows or cares if I actually stood at exactly 38 degrees 39 feet 15 seconds to the North and 106 degrees 27 feet 57 seconds to the West. There are no free socks or race photos waiting for me at the end of FS 863.2E. But in an era defined by self-promotion and the monetization of group validations, this private integrity feels important, even spiritual. You can lie to a lot of people, but don’t ever lie to your dogs.

Spending four, five and sometimes six nights a week in a landscape is to bear witness to time and change. The push to do the implausible and being forced to do it so slowly has created a familiarity I could not have known otherwise. The creaking notes of January trees, the outlandish beauty of the first October snowstorm, the dry height of summer with its flaking mud puddles. They come and always come again. I know these things because I am in them, again and again, in shorts and snow pants and rain jackets and tank tops. I have even learned to love the curling, angry spring winds, as I know they are not unlike the throes of puberty and are simply the necessary harbingers of summer. I now know that the ghostly architecture of an empty hunting camp in late November vibrates with a palpable energy and makes for a fun, spooky lunch spot.

Truthfully, I am not sure what I love more: the valley, the goal or the pursuit. There is so much to do, I rarely go to the same place twice. When an entire area is complete, there is a strange mix of pride and nostalgia. As I look across the various drainages of the Gunnison valley, my heart swells with knowing that I have stood there and there and there.

So if you are out four-wheeling along the top of Steers Gulch or scouting for elk on Maggie Pass and you come across a slow-moving middle aged blonde lady with a black running pack and ugly socks, give me a wave. You’re not likely to see me again.

Sherri Anderson has lived in and wandered about the Gunnison Valley for twenty years. She is happily married, gainfully employed and regularly mortifies her two children on Facebook.